Who do you think you are?

A leader’s evolving self-concept

We all have a self-concept; the term refers to who we understand ourselves to be. It encompasses the attributes that we consider stable (“No matter what situation I’m in, I’m always detail-oriented”) and the roles that we play relative to the others in our life (“I’m more patient as a board member than I am as a CEO”). A healthy and accurate self-concept enables us to derive purpose, value, and meaning from our work: the fruits of our labor provide evidence that we have lived up to our personal remit. In-depth knowledge of one’s own self-concept is especially relevant for executives who must be effective across many settings. In any week, the typical RHR client engages with direct reports, authority figures, peers, customers, shareholders, business partners, and others in the value chain or competitive landscape. The array of roles and relationships can be dizzying, and an effective self-concept is one that enables fluidity across these shifting systems.

Today’s executives must be fast learners and decisive movers. They adapt on the fly, picking up new information, and charting a course amidst complexity and ambiguity. Rarely do they have time to pause and consciously adjust their self-concept so that it accurately reflects the additional knowledge, responsibilities, and positional power that they acquire as their careers progress. We often see clients getting “stuck” in prior self-concepts without realizing it: they stay involved in details or activities that are too low-level rather than stepping up to own the roles and attributes that are most valuable in the present moment. We propose that leaders benefit when they pause to ensure, with intentionality, that they have kept their self-concept up to date. Showing up with a self-concept that is more suited to your prior role(s) is far more career and performance-limiting than wearing last season’s fashions.

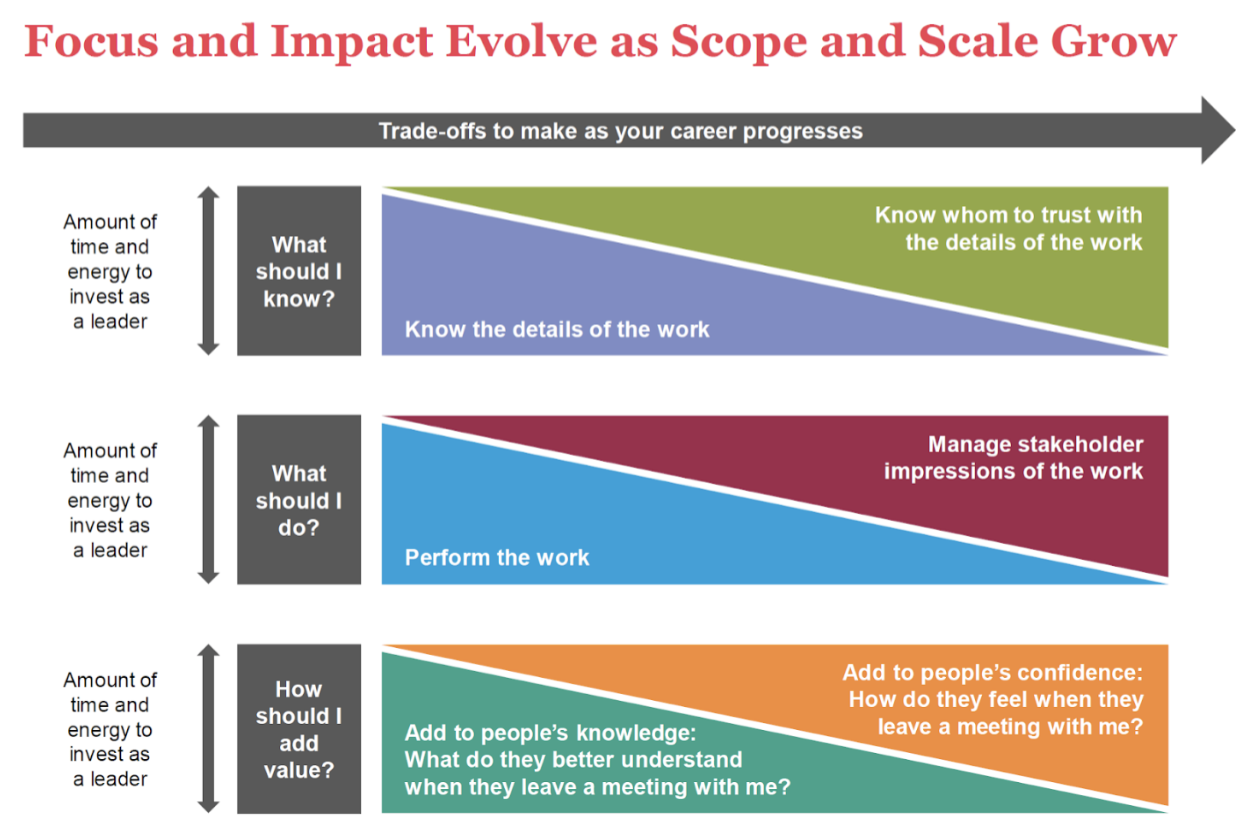

To maintain a current self-concept, leaders need to frame their evolution across three sets of trade-offs. Each requires intentionality: as leaders’ careers and remits grow, their investments of time and energy must evolve. These three trade-offs encompass: what leaders should know, what they should do, and how they should add value.

- As Knowers, we all ground our careers in the fundamentals of our work. Hard-earned knowledge of the business enables an increase in the scope and scale of our accountabilities. As we step up, we are limited by finite human bandwidth and capacity, and we must redirect our awareness and focus to new challenges. Accordingly, we delegate the more granular details to those on our team. In parallel, our self-concept must evolve. Where we previously derived purpose and pride from our in-depth knowledge of the business, we must now gain those good feelings from our knowledge of the people on our teams, and our understanding of their capacity and potential. As Knowers, we transition our expertise to knowing whom to trust with the details and—through self-awareness—knowing what we require from team members who seek to earn our trust.

- As Doers, our initial roles are ones in which the output of our work is concrete—a model, a design, a narrative—and it clearly advances the team’s progress toward a tangible business goal. Over time, expertise in task performance enables us to manage and mentor others who do similar work, and we advance to roles where we define and oversee the work of many. Steady promotions to the point where we are several layers removed from deliverable creation can be disorienting to those who happily identified as top performers or doers. However, to add the value that the organization needs, we must adjust our self-concept to reflect the breadth of our oversight and influence. Our deliverable now is an intangible: we clear the path for those who are creating concrete output. We focus our attention on the stakeholders for whom our team’s deliverables are critical inputs, and we spend our time understanding their needs and adjusting their expectations. To be effective at this work, our self-concept as Doers must reflect the crucial impact of anticipating and removing obstacles and driving broad acceptance of new ideas or methods.

- As Value Adders, early career contributions are grounded in facts and analyses. We feel good when we have illuminated an issue, enhanced others’ understandings, or informed a key decision. As the breadth and depth of our knowledge increases, we grow as mentors and coaches. In lieu of finding the best answer ourselves, it becomes more valuable for us to teach others how to find the answer. Eventually, we transcend the realm of “right answer”: roles at the top traffic in ambiguity, trade-offs, and shifting circumstances. At this point, our self-concept must empower a different Value Add: the most important contribution we can make is to augment others’ confidence rather than their knowledge base. We do this by showing up in ways that integrate inspiration with intellectual humility, coming across as connected and caring even at a distance, and galvanizing performance with a compelling message and presence.

If the concepts described here resonate with you, we encourage you to look at the career trajectory in this visual.

Each of these three trade-offs is represented across a career timeline. Consider each one, and ask yourself, “Where am I currently showing up as a Knower? A Doer? A Value Adder?” If you’ve printed this out, make a mark on each of the three trade-off timelines. Then ask yourself where you need to be in order to be as effective as possible in your current role. If there is a gap to close between those two marks, doing so represents the work of updating your self-concept. We wish you energy and intentionality as you undertake it.