News and Insights

The Art of Leadership

RHR consultants are globally respected leaders in the fields of psychological assessment and leadership coaching/development. Browse our news, articles, and blog posts below.

Webinars & Podcasts

Sign up for our latest webinars, or enjoy previous RHR webinars.

Assessments

Are your leaders prepared to tackle your organization’s critical business challenges? Learn how RHR assessments can reveal pitfalls and potential.

Coaching & Development

One of the quickest ways to enhance business results is with executive coaching. Read our points of view for a roadmap to impressive results in short order.

Board & CEO

Consider the value to your business of a strong board of directors, an effective CEO, and a robust succession plan. See how to create leadership that people want to follow.

Teams

Belonging

Better humans make better leaders. But how to develop better humans? We believe belonging comes from opportunities, access, safety, trust, and advocacy. Read on!

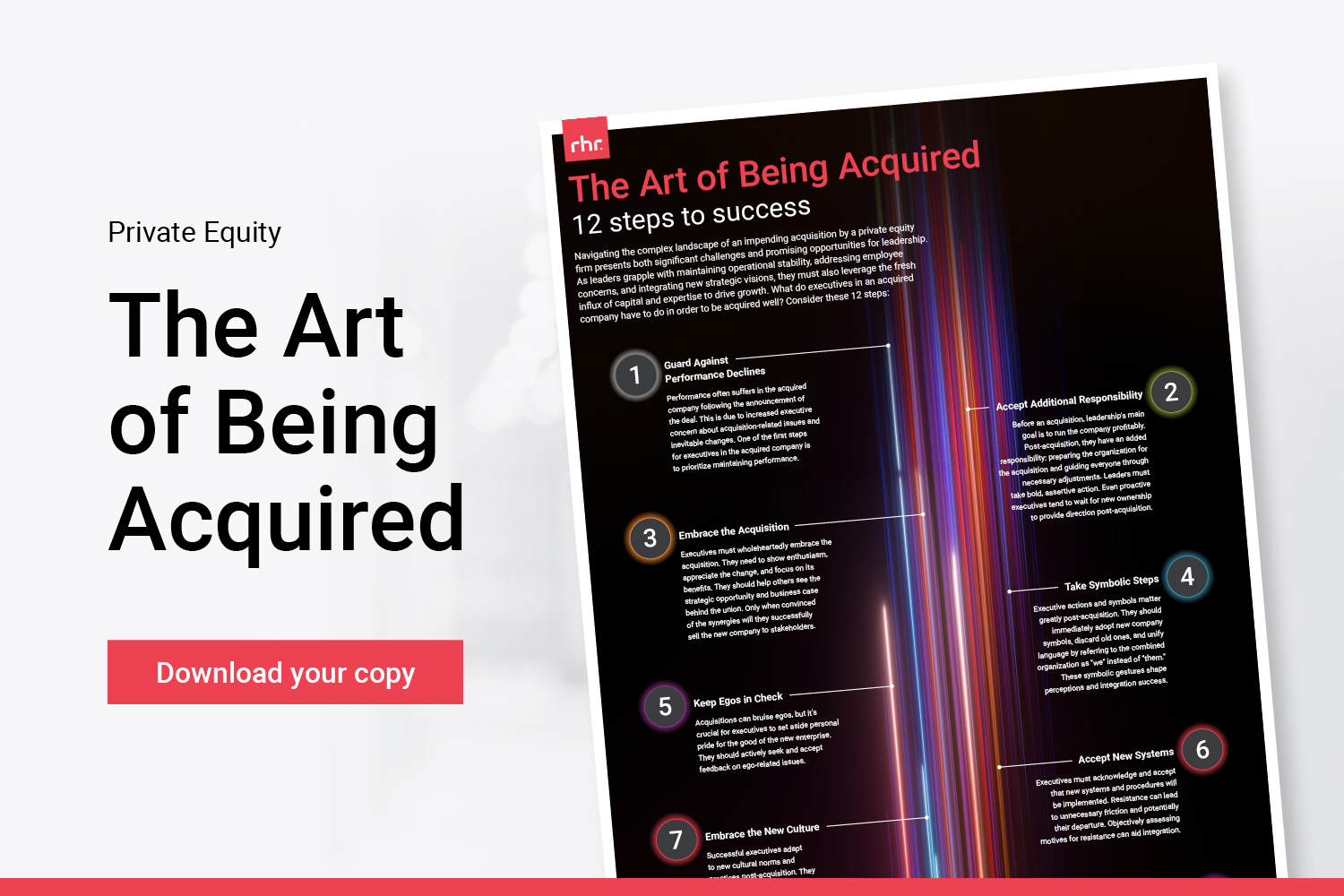

Private Markets

Our unified center of excellence enables us to partner with investor owners and their portfolio companies through every phase of the investment life cycle. Learn how we do it.